The first bridge designed and built under Telford's superintendence was across the river Severn at Montford it was finished in 1792. In the same year we find Telford engaged as an architect in preparing the designs and superintending the construction of the new parish church of St. Mary Magdalen at Bridgenorth. His completion of the church to the satisfaction of the inhabitants brought Telford a commission in the following year to erect a similar edifice at Coalbrookdale. But in the mean time to enlarge his knowledge and increase his acquaintance with the best forms of architecture he determined to make a journey to London and through some of the principal towns of the south of England. He accordingly visited Gloucester Worcester and Bath remaining several days in the last-mentioned city.

He was charmed beyond expression by his journey through the manufacturing districts of Gloucestershire more particularly by the fine scenery of the Vale of Stroud. The whole seemed to him a smiling scene of prosperous industry and middle-class comfort. He then directed his focus to London and during his stay there he carefully examined the principal public buildings by the light of the experience which he had gained since he last saw them. He also spent a good deal of his time in studying rare and expensive works on architecture the use of which he could not elsewhere procure at the libraries of the Antiquarian Society and the British Museum.

There he perused the various editions of Vitruvius and Palladio as well as Wren's 'Parentalia.' He found a rich store of ancient architectural remains in the British Museum which he studied with great care antiquities from Athens Baalbec Palmyra and Herculaneum "so that with the information I was before possessed of and that which I have now accumulated I think I have obtained a tolerably good general notion of architecture."

From London he proceeded to Oxford where he carefully inspected its colleges and churches afterwards expressing the great delight and profit which he had derived from his visit.

He next returned to Shrewsbury Telford proposed to proceed with his favourite study of architecture, but this said he "will probably be very slowly as I must attend to my every day employment" namely the superintendence of the county road and bridge repairs and the direction of the convicts' labour. "If I keep my health however and have no unforeseen hindrance it shall not be forgotten but will be creeping on by degrees." An unforeseen circumstance though not a hindrance did very shortly occur which launched Telford upon a new career for which his unremitting study as well as his carefully improved experience eminently fitted him: we refer to his appointment as engineer to the Ellesmere Canal Company.

The conscientious carefulness with which Telford performed the duties entrusted to him and the skill with which he directed the works placed under his charge had secured the general approbation of the gentlemen of the county. His straightforward and outspoken manner had further obtained for him the friendship of many of them. At the meetings of quarter-sessions his plans had often to encounter considerable opposition and when called upon to defend them he did so with such firmness persuasiveness and good temper that he usually carried his point. "Some of the magistrates are ignorant and some are obstinate he wrote in 1789 though I must say that on the whole there is a very respectable bench and with the sensible part I believe I am on good terms." This was amply proved some four years later when it became necessary to appoint an engineer to the Ellesmere Canal on which occasion the magistrates who were mainly the promoters of the undertaking almost unanimously solicited their Surveyor to accept the office.

Indeed Telford had become a general favourite in the county. He was cheerful and cordial in his manner though somewhat brusque. Though now thirty-five years old he had not lost the humorousness which had procured for him the sobriquet of "Laughing Tam." He laughed at his own jokes as well as at others. He was spoken of as jolly a word then much more rarely as well as more choicely used than it is now. Yet he had a manly spirit and was very jealous of his independence. All this made him none the less liked by free-minded men. Speaking of the friendly support which he had throughout received from Mr Pulteney he said "His good opinion has always been a great satisfaction to me, and the more so as it has neither been obtained nor preserved by deceit cringing nor flattery. On the contrary I believe I am almost the only man that speaks out fairly to him and who contradicts him the most. In fact between us we sometimes quarrel like tinkers, but I hold my ground and when he sees I am right he quietly gives in." Although Mr Pulteney's influence had no doubt assisted Telford in obtaining the appointment of surveyor it had nothing to do with the unsolicited invitation which now emanated from the county gentlemen.

Telford was not even a candidate for the engineership and had not dreamt of offering himself so that the proposal came upon him entirely by surprise. Though he admitted he had self-confidence, he frankly confessed that he had not a sufficient amount of it to justify him in aspiring to the office of engineer to one of the most important undertakings of the day. The following is his own account of the circumstance:

"My literary project is at present at a stand and may be retarded for some time to come, as I was last Monday appointed sole agent architect and engineer to the canal which is projected to join the Mersey, the Dee, and the Severn. It is the greatest work I believe now in hand in this kingdom and will not be completed for many years to come. You will be surprised that I have not mentioned this to you before, but the fact is that I had no idea of any such appointment until an application was made to me by some of the leading gentlemen and I was appointed though many others had made much interest for the place. This will be a great and laborious undertaking but the line which it opens is vast and noble, and coming as the appointment does in this honourable way I thought it too great a opportunity to be neglected, especially as I have stipulated for and been allowed the privilege of carrying on my architectural profession. The work will require great labour and exertions but it is worthy of them all."

Telford's appointment was duly confirmed by the next general meeting of the shareholders of the Ellesmere Canal. An attempt was made to get up a party against him but it failed. "I am fortunate" he said, "in being on good terms with most of the leading men both of property and abilities and on this occasion I had the decided support of the great John Wilkinson king of the ironmasters himself a host. I travelled in his carriage to the meeting and found him much disposed to be friendly." The salary at which Telford was engaged was £500 a year out of which he had to pay one clerk and one confidential foreman besides defraying his own travelling expenses. It would not appear that after making these disbursements much would remain for Telford's own labour, but in those days engineers were satisfied with comparatively small pay and did not dream of making large fortunes.

Though Telford intended to continue his architectural business, he decided to give up his county surveyorship and other minor matters which he said "give a great deal of very unpleasant labour for very little profit, in short they are like the calls of a country surgeon." One part of his former business which he did not give up was what related to the affairs of Mr Pulteney and Lady Bath with whom he continued on intimate and friendly terms. He incidentally mentions in one of his letters a graceful and charming act of her Ladyship. On going into his room one day he found that before setting out for Buxton she had left upon his table a copy of Ferguson's 'Roman Republic' in three quarto volumes superbly bound and gilt.

He now looked forward with anxiety to the commencement of the canal, the execution of which would necessarily call for great exertion on his part as well as unremitting attention and industry "for besides the actual labour which necessarily attends so extensive a public work, there are contentions, jealousies, and prejudices stationed like gloomy sentinels from one extremity of the line to the other. But as I have heard my mother say that an honest man might look the Devil in the face without being afraid, so we must trudge along in the old way."

The Ellesmere Canal

The Ellesmere Canal consists of a series of navigations proceeding

from the river Dee in the vale of Llangollen. One branch passes

northward near the towns of Ellesmere, Whitchurch, Nantwich, and

the city of Chester to Ellesmere Port on the Mersey another

in a south-easterly direction through the middle of Shropshire

towards Shrewsbury on the Severn and a third in a south-westerly

direction by the town of Oswestry to the Montgomeryshire Canal

near Llanymynech. Its whole extent including the Chester Canal

incorporated with it being about 112 miles.

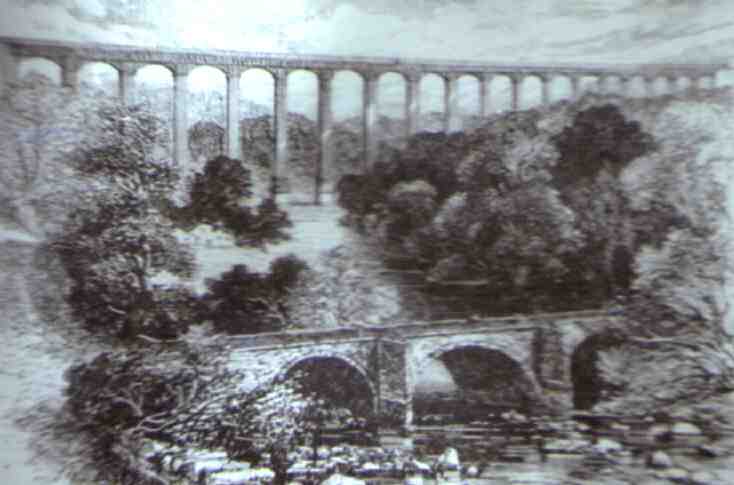

Chirk Aqueduct

Chirk Aqueduct

The aqueduct consists of ten arches of 40 feet span each. The level of the water in the canal is 65 feet above the meadow and 70 feet above the level of the river Ceriog. The proportions of this work far exceeded everything of the kind that had up to that time been attempted in England.

Upon the top of the masonry was set the cast iron trough for the canal with its towing-path and side-rails all accurately fitted and bolted together forming a completely water-tight canal with a waterway of 11 feet 10 inches of which the towing-path standing upon iron pillars rising from the bed of the canal occupied 4 feet 8 inches leaving a space of 7 feet 2 inches for the boat. The whole cost of this part of the canal was £47018.

Return Visit to Eskdale

We now return to Telford's personal history during this period of his career. He had long promised himself a visit to his dear Eskdale and the many friends he had left there but more especially to see his infirm mother who had descended far into the vale of years and longed to see her son once more before she died. He had taken constant care that she should want for nothing. She formed the burden of many of his letters to Andrew Little.

"Your kindness in visiting and paying so much attention to her" said he "is doing me the greatest favour which you could possibly confer upon me." He sent his friend frequent sums of money which he requested him to lay out in providing sundry little comforts for his mother who seems to have carried her spirit of independence so far as to have expressed reluctance to accept money even from her own son.

"I must request that you will purchase and send up what things may be likely to be wanted either for her or the person who may be with her as her habits of economy will prevent her from getting plenty of everything especially as she thinks that I have to pay for it which really hurts me more than anything else." Though anxious to pay his intended visit he was so occupied with one urgent matter of business and another that he feared it would be November before he could set out. He had to prepare a general statement as to the navigation affairs for a meeting of the committee, he must attend the approaching Salop quarter sessions and after that a general meeting of the Canal Company so that his visit must be postponed for yet another month. "Indeed I am rather distressed at the thought of running down to see a kind parent in the last stage of decay on whom I can only bestow an affectionate look and then leave her, her mind will not be much consoled by this parting and the impression left upon mine will be more lasting than pleasant."

He did however contrive to run down to Eskdale in the following November. His mother was alive but that was all. After doing what he could for her comfort and providing that all her little wants were properly attended to, he hastened back to his responsible duties in connection with the Ellesmere Canal. When at Langholm he called upon his former friends to recount with them the incidents of their youth. He was declared to be the same "canty" fellow as ever and though he had risen greatly in the world he was "not a bit set up." He found one of his old fellow workmen, Frank Beattie had become the principal innkeeper of the place. "What have you made of your mell and chisels?" asked Telford. "Oh!" replied Beattie "they are all dispersed perhaps lost." "I have taken better care of mine" said Telford, "I have them all locked up in a room at Shrewsbury as well as my old working clothes and leather apron, you know one can never tell what may happen."

He was surprised as most people are who visit the scenes of their youth after a long absence to see into what small dimensions Langholm had shrunk. That High Street which before had seemed so big and that frowning gaol and courthouse in the Market Place were now comparatively paltry to eyes that had been familiar with Shrewsbury, Portsmouth, and London. But he was charmed as ever with the sight of the heather hills and the narrow winding valley

On his return southward he was again delighted by the sight of old Gilnockie Castle and the surrounding scenery. As he afterwards wrote to his friend Little "Broomholm was in all his glory." Probably one of the results of this visit was the revision of the poem of 'Eskdale' which he undertook in the course of the following spring putting in some fresh touches and adding many new lines whereby the effect of the whole was considerably improved. He had the poem printed privately merely for distribution amongst friends being careful as he said that "no copies should be smuggled and sold."Where deep and low the hamlets lie

Beneath their little patch of sky

And little lot of stars.

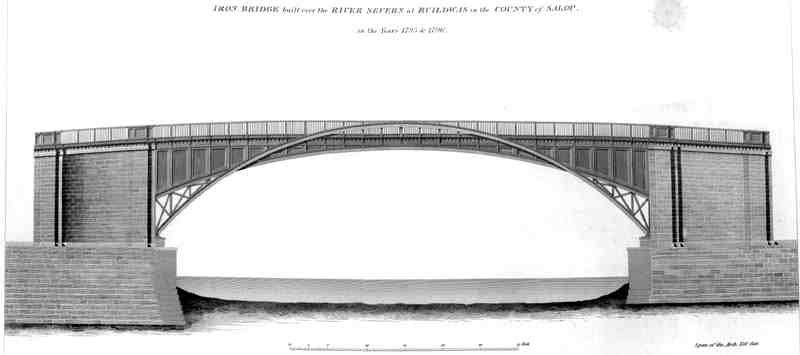

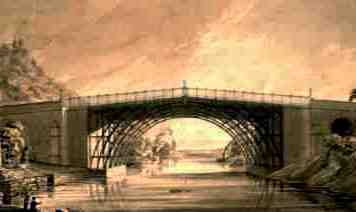

First Iron Bridge - Coalbrookdale

First Iron Bridge - Coalbrookdale

In whatever shares the merit of this great work may be apportioned, it must be one of the earliest and greatest triumphs of the art of bridge construction. Its span exceeded that of any arch then known, being 236 feet with a rise of 34 feet, the springing commencing at 95 feet above the bed of the river and its height was such as to allow vessels of 300 tons burden to sail underneath without striking their masts. Stephenson characterised the bridge as "a structure which as regards its proportions and the small quantity of material employed in its construction will probably remain unrivalled."

Although the span of the new bridge was 30 feet wider than the Coalbrookdale bridge it contained less than half the quantity of iron than the Buildwas bridge, containing 173 tons whereas the other contained 378 tons. The new structure was besides extremely elegant in form, and when the centres were struck the arch and abutments stood perfectly firm and have remained so to this day. But the ingenious design of this bridge will be better explained by the following representation than by any description in words. The bridge at Buildwas however was not Telford's first employment of iron in bridge-building for the year before its erection we find him writing to his friend at Langholm that he had recommended an iron aqueduct for the Shrewsbury Canal "on a principle entirely new" and which he was "endeavouring to establish with regard to the application of iron." This iron aqueduct had been cast and fixed and it was found to effect so great a saving in masonry and earthwork that he was afterwards induced to apply the same principle as we have already seen in different forms in the magnificent aqueducts of Chirk and Pont-Cysyllte.

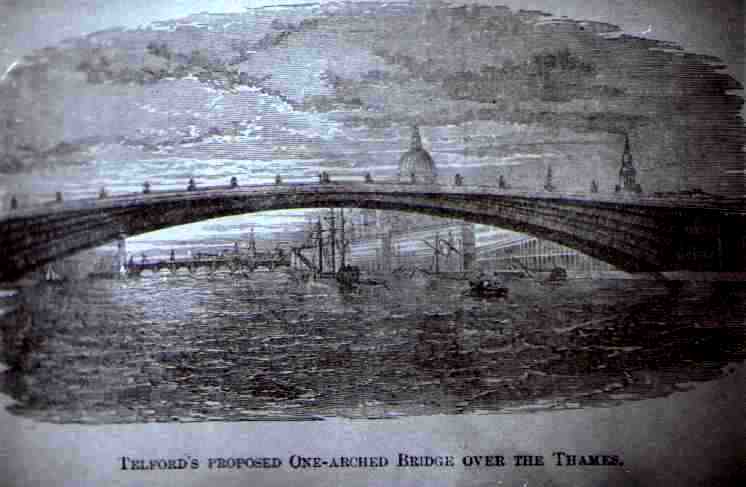

Telford's principal employment of cast iron was in the construction of road bridges in which he proved himself a master. His experience in these structures had become very extensive. During the time that he held the office of surveyor to the county of Salop he erected no fewer than forty-two, five of which were of iron. Indeed his success in iron bridge-building so much emboldened him that in 1801 when Old London Bridge had become so rickety and inconvenient that it was found necessary to take steps to rebuild or remove it, he proposed the daring plan of a cast iron bridge of a single arch of not less than 600 feet span, the segment of a circle l450 feet in diameter. In preparing this design we find that he was associated with a Mr Douglas to whom many allusions are made in his private letters. The design of this bridge seems to have arisen out of a larger project for the improvement of the port of London.

"I have twice attended the Select Committee on the port of London Lord Hawkesbury Chairman. The subject has now been agitated for four years and might have been so for many more if Mr Pitt had not taken the business out of the hands of the General Committee and got it referred to a Select Committee. Last year they recommended that a system of docks should be formed in a large bend of the river opposite Greenwich called the Isle of Dogs with a canal across the neck of the bend. This part of the contemplated improvements is already commenced and is proceeding as rapidly as the nature of the work will admit. It will contain ship docks for large vessels such as East and West Indiamen whose draught of water is considerable."

"There are now two other propositions under consideration. One is to form another system of docks at Wapping and the other to take down London Bridge, rebuild it of such dimensions as to admit of ships of 200 tons passing under it and form a new pool for ships of such burden between London and Blackfriars Bridges with a set of regular wharves on each side of the river. This is with the view of saving lighterage and plunderage and bringing the great mass of commerce so much nearer to the heart of the City. This last part of the plan has been taken up in a great measure from some statements I made while in London last year and I have been called before the Committee to explain. I had previously prepared a set of plans and estimates for the purpose of showing how the idea might be carried out and thus a considerable degree of interest has been excited on the subject. It is as yet however very uncertain how far the plans will be carried out. It is certainly a matter of great national importance to render the Port of London as perfect as possible."

Later in the same year he writes that his plans and propositions have been approved and recommended to be carried out and he expects to have the execution of them. "If they will provide the ways and means and give me elbow room, I see my way as plainly as mending the brig at the auld burn." In November 1801 he states that his view of London Bridge as proposed by him has been published and much admired. On the l4th of April 1802 he writes "I have got into mighty favour with the Royal folks. I have received notes written by order of the King, the Prince of Wales, Duke of York, and Duke of Kent about the bridge print and in future it is to be dedicated to the King."

The bridge in question was one of the boldest of Telford's designs. He proposed by his one arch to provide a clear headway of 65 feet above high water. The arch was to consist of seven cast iron ribs in segments as large as possible and they were to be connected by diagonal cross-bracing disposed in such a manner that any part of the ribs and braces could be taken out and replaced without injury to the stability of the bridge or interruption to the traffic over it. The roadway was to be 90 feet wide at the abutments and 45 feet in the centre the width of the arch being gradually contracted towards the crown in order to lighten the weight of the structure. The bridge was to contain 6,500 tons of iron and the cost of the whole was to be £262,289

Proposed One-arched Bridge over Thames

Proposed One-arched Bridge over Thames

The originality of the design was greatly admired though there

were many who received with incredulity the proposal to bridge the

Thames by a single arch and it was sarcastically said of Telford

that he might as well think of "setting the Thames on fire."

Before any outlay was incurred in building the bridge the design

was submitted to the consideration of the most eminent scientific

and practical men of the day after which evidence was taken at

great length before a Select Committee which sat on the subject.

Among those examined on the occasion were the venerable James Watt

of Birmingham, John Rennie, Professor Button of Woolwich,

Professors Playfair and Robison of Edinburgh, Mr Jessop,

Mr Southern, and Dr Maskelyne.

Their evidence will still be found interesting as indicating the state at which constructive science had at that time arrived in England. There was a considerable diversity of opinion among the witnesses as might have been expected for experience was as yet very limited as to the resistance of cast iron to extension and compression. Some of them anticipated immense difficulty in casting pieces of metal of the necessary size and exactness so as to secure that the radiated joints should be all straight and bearing. Others laid down certain ingenious theories of the arch which did not quite square with the plan proposed by the engineer. But as was candidly observed by Professor Playfair in concluding his report "It is not from theoretical men that the most valuable information in such a case as the present is to be expected."

"When a mechanical arrangement becomes in a certain degree complicated it baffles the efforts of the geometer and refuses to submit to even the most approved methods of investigation. This holds good particularly of bridges where the principles of mechanics aided by all the resources of the higher geometry have not yet gone further than to determine the equilibrium of a set of smooth wedges acting on one another by pressure only and in such circumstances as except in a philosophical experiment can hardly ever be realised. It is therefore from men educated in the school of daily practice and experience and who to a knowledge of general principles have added from the habits of their profession a certain feeling of the justness or insufficiency of any mechanical contrivance that the soundest opinions on a matter of this kind can be obtained."

It would appear that the Committee came to the general conclusion that the construction of the proposed bridge was practicable and safe for the river, was contracted to the requisite width and the preliminary works were actually begun. Mr Stephenson says the design was eventually abandoned owing more immediately to the difficulty of constructing the approaches with such a head way which would have involved the formation of extensive inclined planes from the adjoining streets and thereby led to serious inconvenience and the depreciation of much valuable property on both sides of the river. Telford's noble design of his great iron bridge over the Thames together with his proposed embankment of the river being thus definitely abandoned he fell back upon his ordinary business as an architect and engineer in the course of which he designed and erected several stone bridges of considerable magnitude and importance.

Tongland Bridge

Tongland Bridge

Another of our engineer's early stone bridges which may be mentioned in this place, was erected by him in 1805 over the river Dee at Tongland in the county of Kirkcudbright. It is a bold and picturesque bridge situated in a lovely locality. The river is very deep at high water, there the tide rises 20 feet. As the banks were steep and rocky the engineer determined to bridge the stream by a single arch of 112 feet span. The rise being considerable, high wingwalls and deep spandrels were requisite, but the weight of the structure was much lightened by the expedient which he adopted of perforating the wings and building a number of longitudinal walls in the spandrels instead of filling them with earth or inferior masonry, as had until then been the ordinary practice. The ends of these walls connected and steadied by the insertion of tee stones were built so as to abut against the back of the arch stones and the cross walls of each abutment. Thus great strength as well as lightness was secured and a very graceful and at the same time substantial bridge was provided for the

accommodation of the district.

Amidst all his engagements Telford found time to make particular inquiry about many poor families formerly known to him in Eskdale for some of whom he paid house rent while he transmitted the means of supplying others with coals, meal and necessaries during the severe winter months, a practice which he continued to the close of his life.

Bridging the Dee

"Opposite Compston there is a magnificent new bridge over the Dee. It consists of a single web the span of which is 112 feet and it is built of vast blocks of freestone brought from the isle of Arran. The cost of this work was somewhere about £7,000 sterling and it may be mentioned to the honour of the Stewartry that this sum was raised by the private contributions of the gentlemen of the district. From Tongland Hill in the immediate vicinity of the bridge there is a view well worthy of a painter's eye and which is not inferior in beauty and magnificence to any in Scotland."